Armine G Margaryan: 108th NATO PA Rose-Roth Seminar in Yerevan

Armine Margaryan Spoke at the 108th NATO PA Rose-Roth Seminar in Yerevan

In the framework of the 108th NATO Parliamentary Assembly Rose-Roth Seminar, which took place in Yerevan on 22–23 September 2025, WGSA’s President Armine Margaryan delivered an intervention at the session “Peace Agreement between Armenia and Azerbaijan: The Way Ahead and Remaining Challenges” and responded to questions from participants.

The session was moderated by Dennis Sammut (LINKS Europe Foundation) and featured contributions from Nigar Göksel (International Crisis Group) and Murad Muradov (Topchubashov Center).

Below is the full text of Armine Margaryan’s speech:

Excellencies, Distinguished Colleagues, Ladies and Gentlemen,

It is a privilege to join you today for the NATO Parliamentary Assembly’s Rose-Roth Seminar, and to contribute to this timely discussion.

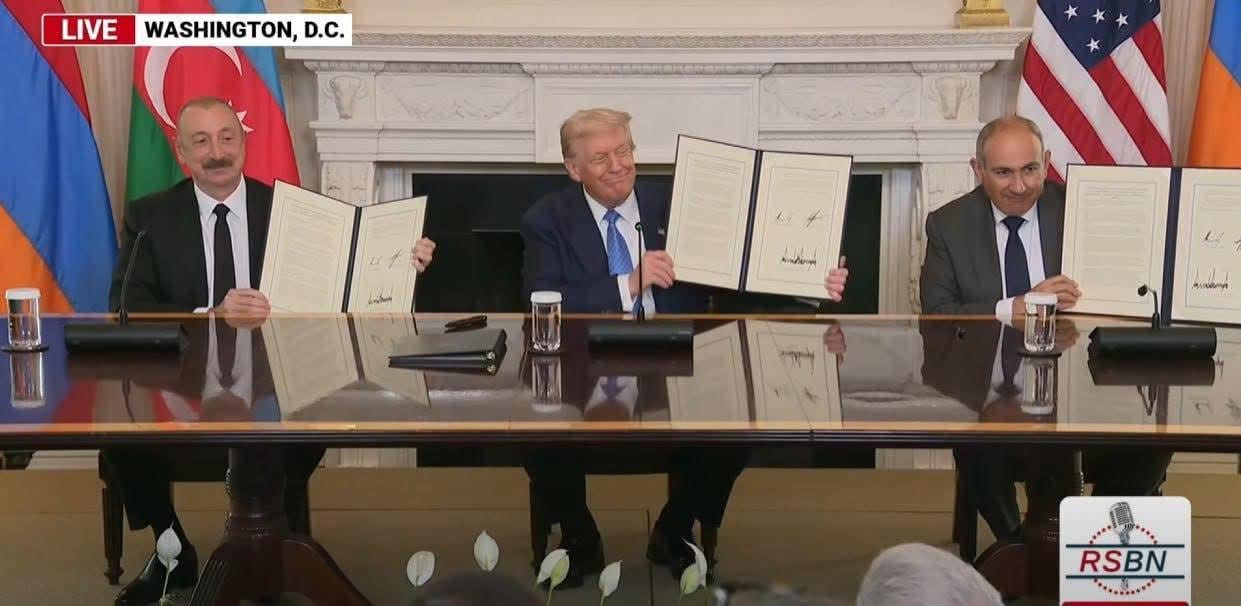

For the first time, when speaking about this topic, I can begin with a note of cautious optimism. On August 8, 2025, in Washington, Armenia and Azerbaijan initialed the long-negotiated Agreement on the Establishment of Peace and Inter-State Relations. This moment, after more than three years of tough negotiations, was historic. It offered a real chance to finally turn the page on over 3 decades of bloody conflict.

And I cannot resist emphasizing the enormous efforts of my country in reaching this point, despite the forcible displacement of Nagorno-Karabakh Armenians from their ancestral homes, Azerbaijan’s coercive diplomacy, its use and constant threat of force, and its anti-Armenian rhetoric at the highest level. Armenia has stayed firmly committed to the peace agenda, an agenda that comes from the grassroots and is rooted in the belief that the societies of Armenia and Azerbaijan deserve a just and durable peace.

A few days after the Washington Summit, the text of the agreement was made public, providing concrete answers to concrete questions for the societies of Armenia, Azerbaijan, and for the international community, while also revealing the remaining challenges, and reminding us that although progress has been made, the hardest work still lies ahead.

First, the agreement is framed in reciprocal terms: what is obligatory for Armenia is obligatory for Azerbaijan, and vice versa. Both sides pledged not to raise territorial claims against each other, now or in the future. For me, as someone coming from Armenia’s think tank community, this provision is especially important, given the so-called “Western Azerbaijan” narrative. This narrative, repeatedly voiced by Azerbaijan on the highest level, essentially questions Armenia’s territorial integrity and is perceived in our society as a direct claim against Armenia itself. Unless this rhetoric – and I will even say strategy – is abandoned, even after the signing of the Peace Agreement it will remain a serious obstacle to building trust and could undermine the peace process.

Second, Armenia and Azerbaijan recognized that the boundaries of the former Soviet republics have become the international borders of their independent states, along with recognizing each other’s territorial integrity and sovereignty. What does this mean in practical terms? Following Azerbaijan’s offensives against Armenia in 2022, Azerbaijan currently holds more than 200 square kilometers of Armenian land. Armenia, in turn, controls only a few small strips of Azerbaijani territory from the first Nagorno-Karabakh war.

The Peace Agreement makes clear that these issues must be resolved through negotiations between the respective border commissions, in line with agreed regulations, in order to conclude an agreement on delimitation and demarcation of the state border. In other words, the use of force is no longer on the agenda, and the text of the Agreement is unambiguous about that.

Third, neither Armenia nor Azerbaijan may invoke internal legislation as justification for failing to implement the Agreement. I believe this is a strong foundation for addressing long-standing concerns on both sides. Azerbaijan has repeatedly raised concerns regarding Armenia’s Constitution, pointing to the reference in its preamble to the Declaration of Independence, which mentions Nagorno-Karabakh. On the highest level, Azerbaijan has gone so far as to directly link the final signing of the peace agreement to constitutional reform in Armenia.

Let me emphasize that debate on the necessity of constitutional reform in Armenia began long before such demands. At the same time, for most Armenians, this linkage is perceived as interference in our internal affairs, something that not only undermines confidence-building measures, but also risks affecting the outcomes of the referendum itself. Moreover, Armenia is a democratic state. No one can predict the outcome of the referendum, and if the majority votes “no,” what then? More war? Continued conflict?

What I want to stress is that the agreed provision in the treaty removes this obstacle entirely: nothing prevents Azerbaijan from signing the agreement tomorrow, as Armenia stands ready despite the fact that Azerbaijan’s own Constitution still contains references that amount to territorial claims on nearly sixty percent of Armenia’s sovereign territory.

Fourth, the August 8 Washington Summit is remarkable not only for the initialing of the peace agreement but also for the joint Armenia–Azerbaijan–U.S. declaration facilitated by President Donald Trump. Its centerpiece is the “Trump Route for International Peace and Prosperity” (TRIPP). This initiative is about opening communications between Armenia and Azerbaijan for intra-state, bilateral, and international transportation, based on respect for sovereignty, territorial integrity, and jurisdiction. In practical terms, Azerbaijan would gain a connection to its Nakhichevan exclave through Armenian territory, while Armenia would receive reciprocal benefits for international and intra-state connectivity. While the details remain to be negotiated, this provision opens a window of opportunity for regional interconnectivity that could strengthen peace and stability. Moreover, it eliminates artificially created, the so-called “Zangezur Corridor” narrative of Azerbaijan, which was used to pressure Armenia into conceding an extraterritorial corridor through its Syunik region. Every time this “corridor” narrative resurfaces, it contradicts the very foundations of the Armenia–Azerbaijan–U.S. joint declaration.

And finally, let me turn to the humanitarian dimension, which is the most emotional part of the peace process: the fate of Armenian prisoners of war. Their release remains one of the most critical confidence-building measures between Armenia and Azerbaijan, and it is an issue that cannot be left unresolved if we are serious about building peace.

Let me conclude with this: the conflict has deep roots. Each society has its own truth; each has its own pain; both societies do not trust each other. But two points should guide us if we want to make the peace process irreversible. First, geopolitics can change, but geography does not. Second, both governments must prepare their populations for peace every single day through their rhetoric and through their policies.

Thank you.

Share this content:

Yorum gönder