Huriye Yıldırım Çınar: Sahel on fire: Mali’s crisis of legitimacy and limits of military solutions

Mali has in recent years become the stage for one of Africa’s most severe security crises. The regime of Assimi Goita, who seized power through a military coup in 2020 by toppling President Ibrahim Boubacar Keita, now finds itself trapped between Tuareg insurgents, terrorist organizations and economic collapse.

In early November 2025, the advance of the al-Qaida-affiliated group Jama’at Nusrat al-Islam wal-Muslimin (JNIM) toward the capital Bamako sparked international debate over whether the Malian state was on the brink of collapse. Beyond its physical advance, JNIM’s blockade of major routes across the country has paralyzed fuel distribution for weeks, disrupting daily life nationwide. As the crisis deepened, several countries, including the United States and the United Kingdom, issued travel warnings and urged their citizens to leave Mali.

From the 1960s to Goita

The current security and governance crisis in Mali can be understood through a historical lens. Although Mali gained its political independence from France in 1960, the country remained subject to France’s neocolonial influence in political, military and socio-economic affairs for decades. Modibo Keita, the first post-independence president, adopted socialist policies, but his rule was overthrown in a 1968 military coup, ushering in a long era of political instability.

Between March 22-26, 1991, a wave of nationwide protests, led mainly by students, demanded an end to military rule and a transition to democracy. These demonstrations, later known as the “March Revolution,” were violently repressed by security forces, leaving around 300 people dead. However, segments of the army refused to open fire and joined the protesters. As a result, dictator Moussa Traore was ousted, paving the way for a transition to multiparty democracy in 1992.

Yet the multiparty system failed to bring lasting political stability. The Tuareg uprising in northern Mali in 2012, compounded by the spread of extremist organizations, plunged the country into chaos. The state collapsed in the north, and the Malian government sought salvation through French-led interventions – Operation Serval (2013) and later Operation Barkhane. However, France, the former colonial power, failed to deliver the expected security outcomes. Its counterterrorism strategies, largely detached from local realities, further destabilized Mali’s security landscape.

Consequently, two successive coups in 2020 and 2021 brought Colonel Assimi Goita to power. Goita’s regime came to prominence with the promise of addressing Mali’s security challenges, especially in the country’s north, where Tuareg separatists and extremist groups remain the key threats.

Mali under JNIM terror

In March 2017, four extremist movements – Ansar Dine, al-Mourabitoun, the Macina Liberation Front (Katiba Macina) and al-Qaida in the Islamic Maghreb’s (AQIM) Saharan branch – merged under Iyad Ag Ghaly’s leadership to form the JNIM.

The JNIM merger sought to unify diverse local and transnational extremist networks under a single structure. The JNIM positioned itself as al-Qaida’s Sahelian affiliate, adopting a decentralized structure built around regional katibas and local leaderships, which allowed it to adapt to local dynamics and connect with ethnic and criminal networks.

Three factors explain JNIM’s growing influence: exploitation of governance vacuums, the adoption of “economic warfare” tactics targeting logistics and trade networks, and a hybrid strategy combining coercion with limited service provision. Beyond guerrilla tactics, the group began targeting transport convoys and logistics routes, weaponizing the state’s economic vulnerabilities. In recent years, the JNIM has also expanded its tactics to include drone attacks, road blockades, taxation systems under the guise of “protection fees,” and coordinated assaults on transport networks.

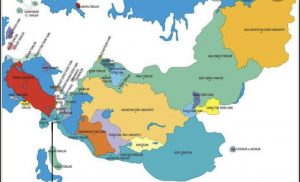

Geographically, JNIM’s operations have expanded from northern and central Mali into Burkina Faso, Niger, and, since 2024, coastal states such as Benin. The group’s growing presence in western Mali (in the Kayes region) and near the Mauritania-Senegal border underscores its transnational reach. By offering rudimentary justice and security in ungoverned areas, the JNIM has cultivated localized legitimacy, though its rule is accompanied by harsh sharia enforcement, human rights abuses, and severe social restrictions.

The group’s recent economic blockade campaign has taken center stage in Mali’s 2025 crisis. Throughout the summer, JNIM targeted fuel convoys and transport companies along the Kayes-Nioro corridor, destroying hundreds of tankers and isolating Bamako. These attacks have caused fuel shortages, price spikes and supply chain disruptions, paralyzing daily life and exerting psychological and political pressure on the regime. The JNIM’s efforts to control territory and impose governance structures indicate a long-term contest for political legitimacy and state authority that military interventions alone cannot resolve.

A family of Malian refugees rests after crossing into Mauritania, as they fled the blockade imposed on their city by the JNIM, which tightened its grip on the increasingly weakened Malian military regime, Douankara border point, Fassale, Mauritania, Nov. 4, 2025. (AFP Photo)

A family of Malian refugees rests after crossing into Mauritania, as they fled the blockade imposed on their city by the JNIM, which tightened its grip on the increasingly weakened Malian military regime, Douankara border point, Fassale, Mauritania, Nov. 4, 2025. (AFP Photo)

Goita tries to find solutions

In response, the Goita regime has distanced itself from France and turned toward Russia for security cooperation. Since 2021, the Wagner Group has operated in Mali, assisting counterterrorism operations and internal security missions. The joint recapture of the symbolically significant city of Kidal initially appeared to mark a success for the Mali-Russia partnership.

However, this cooperation proved unsustainable due to regional instability and Wagner’s own structural weaknesses. Intense clashes between Malian and Wagner forces on one side, and the JNIM and Tuareg fighters on the other, erupted along the Mali-Algeria border in July 2024, resulting in heavy casualties. Reports that Ukraine may have shared intelligence with Tuareg forces against Wagner illustrated the complex, internationalized nature of Mali’s conflict.

The regional security environment further deteriorated following the 2023 coup in Niger, which led to fragmentation within the Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS) and the creation of the Alliance of Sahel States (AES) – a military and political pact between Niger, Mali and Burkina Faso. Established through the Liptako-Gourma Charter on Sept. 16, 2023, the AES was conceived as a response to Western disengagement and ECOWAS sanctions against military regimes. The alliance sought to assert “regional strategic autonomy” and build an alternative security framework independent of Western influence.

However, the AES faces severe limitations. Its member armies lack professionalization, logistical depth and intelligence capabilities. Russia’s and Wagner’s support provides temporary military gains but fails to generate lasting institutional strength. Moreover, these states face diplomatic isolation, economic sanctions and restricted access to international financial institutions after distancing themselves from ECOWAS. For now, AES represents more of a political statement of sovereignty and anti-Western solidarity than a functional military alliance. Its long-term success will depend on rebuilding civil-military relations, institutional reform, and public support, conditions that remain elusive in the current context.

Ultimately, despite more than three decades of democratization and state-building efforts, Mali remains a fragile state with weak institutions and deep security vulnerabilities. The democratic values gained through the 1991 popular uprising never evolved into a durable political culture due to corruption, ethnic divisions and the absence of strong institutions.

Since 2012, the collapse of state authority in the north and the rise of extremist movements have entrenched a cycle of insecurity. The Goita regime’s security-centric governance provides short-term control but neglects governance, development and reconciliation, thereby undermining prospects for sustainable stability.

The greatest risk Mali faces in the near and medium term is the erosion of state legitimacy and the consolidation of JNIM as an “alternative authority.” While the AES framework and Russian support offer symbolic solidarity, they lack institutional resilience and sustainability. Mali’s path to absolute stability depends on inclusive governance, local reconciliation and regional cooperation, rather than temporary military solutions. Otherwise, the country risks descending into a prolonged “silent collapse” masked by fleeting military victories.

About the author

Assistant professor at the Department of International Relations in Van Yüzüncü Yıl University

Published by Daily Sabah on 24 November 2025

Share this content:

Yorum gönder